Juicing Machine: Fresh Idea from Hokitika

The New World supermarket in Hokitika on the west coast of New Zealand has something I didn’t know I needed until I saw it—a self-serve juicing machine. I love orange juice but hate packaging waste. Now, I can bring my own bottle to refill with fresh-squeezed deliciousness, which seems like a win for sustainability. But which is really most sustainable: refrigerated packaged juice, frozen concentrate, or fresh juice from fruit?

I’m not the first person to wonder which type of juice is most planet-friendly, and it turns out that a deep dive into the sustainability of juice has insights into the sustainability of agriculture more generally. Angela Hayes, writing in Stanford Magazine in 2012, fielded this question from a reader: Frozen concentrate or straight-from-the-carton: Which juice uses less energy to produce/ship/store? Her conclusion: go with straight-from-the-carton. She based this advice on a juice lifecycle assessment by The Earth Institute at Columbia University at the request of PepsiCo’s Tropicana. As a result of that study, Tropicana Pure Premium Orange Juice became the first consumer brand in North America to be independently certified by the Carbon Trust.

Biggest Impact: Growing the Fruit

The Tropicana lifecycle study determined that 60% of the carbon footprint of its orange juice was from agriculture and manufacturing, 22% was transportation and distribution, 15% was packaging, and 3% was consumer use and disposal.

PepsiCo enlisted Columbia University's Earth Institute and the environmental-auditing firm Carbon Trust to help assess the carbon footprint of each half gallon of its Tropicana orange juice. The sustainability initiative found that on average the process, from growing the oranges to getting a 64-oz. carton of healthy goodness into your fridge, involved emitting 3.75 lb. of greenhouse gases. And the single biggest contributor to Tropicana's carbon footprint wasn't the gas-guzzling trucks that deliver the cartons to stores or the machinery used to run a modern citrus facility. It was the fertilizer for the orange trees, which accounted for a whopping 35% of the OJ's overall emissions. That came as a surprise even to the people doing the accounting. "We thought it might be transport or packaging," says Tim Carey, PepsiCo's sustainability director. "But the agricultural aspects of the operation are more important than we expected."

Less is More

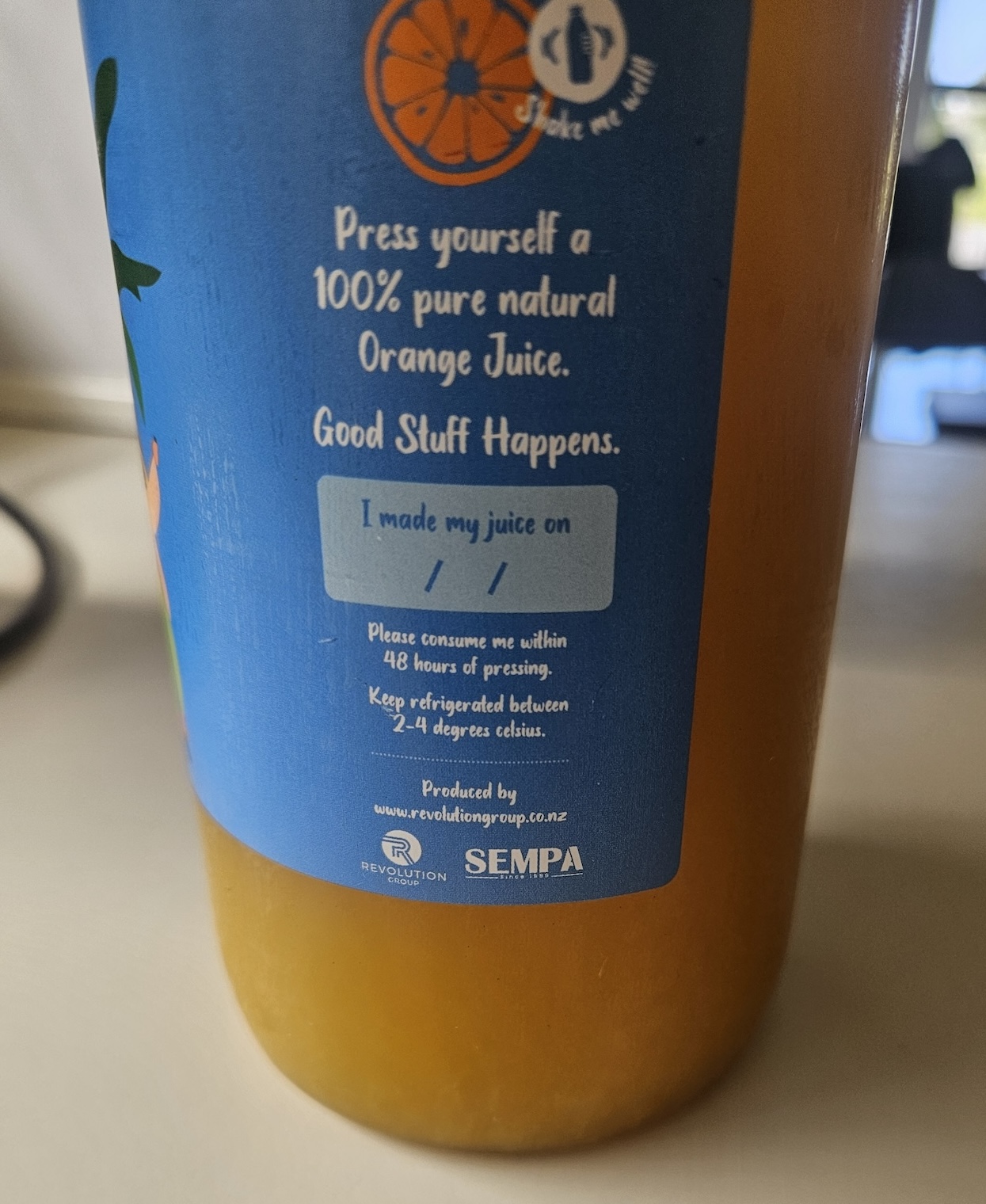

For the first bottle of squeezed-in-store juice, I had to pick up an empty bottle next to the machine so that they could scan the bar code at check out. But after that, I reused my bottle, avoiding the need for more bottles. Assuming the Tropicana data applies here in New Zealand, that cut the carbon footprint of refills by 15%. Valencia oranges go in the machine, and juice comes out. No packaging required!

Besides no packaging, freshly squeezed juice also requires no pasteurization or freezing. When orange juice is processed at a plant to be packaged as “Not From Concentrate,” it is heated to 160 degrees Fahrenheit for a minimum of six seconds to kill bacteria. Juice for “Frozen Concentrate Orange Juice” is heated to evaporate off water and then frozen at 20 degrees Fahrenheit for storage. Furthermore, once the juice is out of the orange, it has to be kept cold immediately. But oranges waiting to be squeezed can be stored at room temperature for a week, their peels naturally keeping the juice inside from spoiling.

So far the sustainability story of fresh-squeezed orange juice is pretty good: less packaging and less energy required. And by having the juicing machine at the store, that saves the need for every customer to have their own juicer at home. Another point for sustainability!

More to the Story

Whenever I’m considering the sustainability of food, I start with the price per unit. That isn’t a perfect reflection of environmental impacts, but it’s better than trying to do a lifecycle analysis on your own. The price of food generally has to cover all the costs to produce it. When local produce is in season, the price drops. This is in part due to supply and demand but also reflects the fact that the produce doesn’t have to be shipped long distances. If you want to eat locally grown fruits and vegetables in season, a good place to start is to see what’s on sale in your local grocery store.

On the other hand, organic produce is usually more expensive than produce that doesn’t meet organic standards. Some of that extra cost is the expense to get certified, but some of the cost premium is lower productivity per acre of land. The central challenge of agriculture is to increase current productivity in ways that don’t diminish future productivity. The price of organic produce relative to non-organic produce has dropped in many cases as sustainable organic methods become more productive.

The price of fresh-squeezed orange juice at the New World market is $9.99 per liter. In the same store, Keri Juice Kitchen Premium Orange Juice is $3.05 per liter. That gives me pause to pronounce fresh-squeezed as truly more sustainable. Why is fresh-squeezed so much more expensive?

One reason for the higher price might be that fresh fruit is bulkier and more perishable than pasteurized juice. Once picked, an orange lasts about a week unrefrigerated and about four weeks if refrigerated. Pasteurized juice, on the other hand, lasts dozens of weeks. Picking fruit and then quickly pressing juice probably results in far fewer rotten oranges than picking fruit, shipping it to grocery stores, and then storing it until a customer squeezes the juice out of it. A higher rate of wasted fruit could completely wipe out any sustainability gains from eliminating packaging and pasteurization.

The juicer isn’t being supplied with organic oranges, so that isn’t the reason for the price difference. But when I shopped at the store one night, I noticed that the juicer wasn’t on the sales floor. It was being cleaned, along with all the deli equipment, and then wheeled into the backroom to be stored overnight. Besides that, all day long, the machine must be monitored, new oranges loaded, and peels taken away. My guess is that the labor costs to provide the fresh-squeezed juice experience are the majority of the price premium. Every day, the machine has to be set up, managed all day, then taken down, taken apart, and carefully cleaned. It’s a constant battle against microorganisms—the fungus and bacteria who like orange juice just as much as we do!

A final consideration is the profit margin the store makes. Supermarkets typically operate on razor-thin margins of 1% or 2%. They are a volume business. But offering fresh-squeezed orange juice is an opportunity to increase those margins. If you really like orange juice, you’re willing to pay more for fresh juice.

More Sustainable or Not?

I guess that it’s a close call whether fresh-squeezed or bottled juice is more environmentally sustainable. If you like the idea of providing jobs for supermarket workers, then fresh-squeezed juice is a win because it clearly requires more labor, even though customers are pushing the button to make the juice. Fresh-squeezed juice is also a great way to eliminate plastic waste, a major scourge on the planet right now. On the other hand, it seems probable that shipping oranges rather than bottles of juice results in more rotten fruit.

Cases like this, comparing different ways to produce orange juice, show the importance of certification standards. By conducting a complete lifecycle analysis of their product, Tropicana was able to identify and implement more sustainable practices. As consumers, we can choose to buy from companies that do due diligence to ensure that they are continually improving their practices.

Personally, I’m fine with choosing fresh-squeezed orange juice. I know that the most sustainable choice for hydration is tap water; orange juice is an indulgence. I understand the food safety recommendation to drink the whole bottle within 48 hours, but I’m willing to take the risk to use my eyes and nose to determine whether my unpasteurized juice is still good and stretch each bottle to last a week. Rather than agonizing over whether to buy bottled juice or fresh-squeezed, I’m limiting the amount of juice I drink and getting maximum enjoyment from every sip.

What’s Next for Dispatches and Sustainable Steps

Until I return to the United States in May, we’ll continue alternating each week between a sustainable dispatch from New Zealand and an action guide for sustainability. We’re now starting to explore the pathway to sustainable food. What we eat is a daily opportunity to make a positive environmental impact, but it’s a challenge to be well-informed since food preferences are so personal and food policy provokes such passionate debates. We provide well-researched, science-based action guides so you can make wise decisions that align with your values. Stay with us on the journey to sustainability as we take action to have a positive impact on the world.

References and Further Reading

Getting the Most Sustainable Squeeze from your OJ: Essential Answer, Stanford Magazine

Tropicana is first U.S. brand to be Carbon Trust-certified, Packaging World

What Are Valencia Oranges?, allrecipes